Conserving abandon

The Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale on the edge of the Bois de Vincennes is a curious relic of France’s colonial past. Yesterday I joined Adam of Invisible Paris for a guided tour of the garden in springtime, and it struck me that it raises some fascinating issues about landscape conservation.

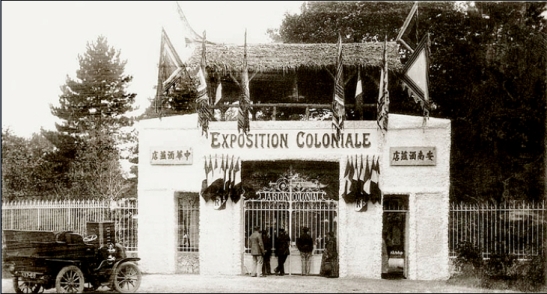

Created in 1899 to test and redistribute plants from the country’s territories abroad, the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale was the site of a Colonial Fair in 1907 which used displays of plants and buildings to provide a sense of the French colonies for well-to-do Parisian visitors. Elephants and camels were brought in and, extraordinarily, so were des indigènes – people literally shipped in from the colonies to live in huts and tents in the garden and be gawped at by visitors. Adam showed us some wonderful 1907 photographs of the Fair’s buildings, with elephants careering down a specially created water slide, and the indigènes wrapped in blankets against the Northern European chill, staring stoically at the camera.

Created in 1899 to test and redistribute plants from the country’s territories abroad, the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale was the site of a Colonial Fair in 1907 which used displays of plants and buildings to provide a sense of the French colonies for well-to-do Parisian visitors. Elephants and camels were brought in and, extraordinarily, so were des indigènes – people literally shipped in from the colonies to live in huts and tents in the garden and be gawped at by visitors. Adam showed us some wonderful 1907 photographs of the Fair’s buildings, with elephants careering down a specially created water slide, and the indigènes wrapped in blankets against the Northern European chill, staring stoically at the camera.

The entrance to the 1907 Colonial Fair. Image from http://www.expositions-universelles.fr

The human attractions disappeared after six months (sadly no records remain of their experiences or their ultimate fate) but the buildings and the plants were left in situ after the Fair ended. The site became a hospital during the First World War and home to memorials for colonial soldiers morts pour la France (killed in the service of France).

Some of the buildings were co-opted for other uses, but over the decades that followed most of the site fell into disuse and neglect. Some structures burnt down or were destroyed by weather or time. The exotic plant species gradually died out, to be replaced by volunteer trees and vegetation. The only remaining original plantings are some persimmon, lots of bamboo and a single eucommia ulmoides, or Chinese rubber tree.

Then in 2003 the city of Paris took over the site. It trumpeted its wish to restore the garden and its listed colonial structures, and run it as a model of sustainability. A beautifully illustrated book was published about the garden and its history, the Indochina pavilion was expensively restored, and signs of sustainability – such as a mass of beehives – started to appear on site.

But the management of this garden raises some difficult questions. Without an obvious new use for the buildings, why invest the large sums needed to restore and maintain them? The story of French colonisation is undoubtedly important, but it is an awkward – sometimes shameful – part of the country’s history, and so is it likely to provide a popular visitor attraction? In any event, what value do these buildings have historically, as quickly constructed French interpretations of vernacular architecture in Asia and Africa? The garden may be owned by the city of Paris, but it is located in the leafy suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne; how far should Parisian tax revenue be spent restoring a site away from the city?

But if the city does not restore the garden, then its options are limited. Some might argue that the garden should simply be left to continue to decay and eventually disappear, remembered only through old photographs and stories. Such abandon has a certain romantic appeal, while dilapidated structures and wilderness could be a suitable metaphor for the bygone values and beliefs of colonisation.

At the moment, the city seems to be trying to find a middle way between these two approaches. Its staff are trying to stabilise decaying structures and to keep the garden accessible and safe for visitors, by clearing paths, putting up warning signs and fences, and cordoning off dangerous areas. Save for planting the odd new tree, little is being done to change the existing vegetation. Instead the city argues that it is preserving both the mysterious charm and the biodiversity of the site.

To be honest, it feels to me like an uneasy compromise – essentially trying to conserve the sense of history and neglect, while keeping the space safe and useable. The garden is no longer abandoned, but is being managed to appear as if it is. But I have no easy solutions for what else could be done.

With thanks to Adam for a fascinating tour of this little-known garden, and for allowing us to to ponder on the many issues it raises.

This is an interesting situation, with the remains of some very temporal buildings and site design becoming permanent through perception, so that they can be neither destroyed nor faithfully restored.

Your take on the uneasy compromise is just right: a state of suspended animation is going to be expensive and difficult to maintain, and what is it capturing, or preserving?

Jill, What an interesting site with a very checkered history–more dark than not. It raises some very “deep” issues about history and conservation. I agree with you (or what I think you concluded) that the garden cannot add much to an understanding of colonial times and exploitation and so may not hold much historical value. Thanks for a thought-provoking post. Carolyn

I was waiting for your “Obscura” journey post. I guess it is not the only garden in these conditions, caused mostly by a myriad of complications: who should be taking decisions, what can it be done, why should it be preserved, funding needed, …. and many more questions you already posted. And on top of it there is the side effect of colonialism and political decisions. Nevertheless, I believe these are repositories of knowledge, and the society need them to to learn. Thanks for sharing!

It’s so odd how landscapes become symbols of a whole era. If the buildings were just seen as ordinary old, slipshod, falling-to-ruin fire hazards, none of these issues would be a problem, but instead they’re laden with all kinds of associations. Like you suggest, letting it stay *officially* delapidated might be a tacit way of saying, “Yes, we did this at one time, but we don’t uphold the exploitation of colonialism any more.” Both the “yes” and the “but” have to be in there somewhere.

It sure sounds like the garden went pretty quickly from being a useful place (more scientific/commercial?) to buying wholesale into exoticism/Orientalism. Any idea why the change?

Thanks for coming along Jill, and for this very interesting reflection that you have posted following the event. I meant to ask you about the traces of tropical flora that remain on site, and will now have to go back and hunt out the rubber tree!

Some interesting discussion here in the comments too. Stacy – in answer to your question as to why it changed so rapidly, I think the answer is that it always had a dual purpose. It had a scientific role to play, but those in charge always wanted to attract visitors too. That period corresponded with a fashion for these ‘exotic’ colonial events, and the temptation to slip into that world proved too great. However, it can be said that it was a success for them, as they attracted nearly 2 million visitors in the 6 months the exhibition ran, and perhaps more importantly, they also managed to keep some of the extra space they had requisitioned when organising the event.

Thanks, Adam – Yes, I can see where a “living museum” of sorts would attract more visitors than agronomy plain and simple.

Thanks for the interesting comments. The site is strangely unsettling for a number of reasons, even on a beautiful Spring day, with its overgrown vegetation, ramshackle old structures, and security fences and tape. The memory of those people shipped in as exhibits from Africa and Asia, caught so poignantly in early photographs, somehow lingers. Plus we were just about the only visitors, so you feel almost as if you have stumbled into a disturbing dream. I guess that is the sense the city is trying to preserve, rather than some hard-edged, challenging reminder of the realities of colonialism.

It would be interesting to do more analysis of the garden’s vegetation – how much was deliberately introduced, and how much has just appeared, and from where. My information on the three exotic species that remain from the original garden comes from the city’s website. I don’t know if someone has been able to compare original planting plans with existing vegetation, or if it was simply a case of spotting exotic species that looked about a hundred years old… We certainly saw lots of bamboo on our visit. The persimmons would be easy to spot in late Autumn, with their squat orange fruit. But good luck, Adam, locating the Chinese rubber tree! It is not very distinctive: I guess it will be about 20 metres high by now, with shiny, fairly narrow, dark green leaves. Apparently if you scrap off a little piece of bark, you will find some stringy latex, hence the tree’s common name. Let us know if you find it!

What an interesting conflict in the overlap of history, conservation and politics. This location reminds me of ghost towns of the southwestern part of the United States. The haunting aspect of the location strikes that same chord within me.

O dear, what a splendid opportunity lies here! First, it needs a botanist trained in tropical botany to identify what remains, and whether these were intended for commercial, agricultural, or ornamental use, or whether they were simply meant to show the French what tropical plants looked like.

Next, a botanist trained in food history re: the foods brought from the colonies that became a significant part of the European diet. For example, corn, tomatoes, and potatoes are all New World foods that have widely adopted into the Old World diet. Depending on species, bamboo may be used as timber or a delicacy. It would be hugely interesting and informative for many to know where the foods they eat originated, and that, too, is part of the legacy of colonialism.

Are there any existing maps of the original planting schemes? Is it worth replicating, perhaps with plants in containers that could moved indoors for the winter?

Ohhh, putting it back together could be such fun. All it needs is a clear master plan, a couple of botanists and horticulturalists, someone to organize volunteers, and voila! Another delightful historical oddity preserved.

Sara, I admire your enthusiasm! It could indeed be fun to try to recreate the original scientific garden, or the exhibition displays, but I’m left with that lingering question about the purpose of such a project. Would it be worthwhile or popular enough to justify the cost, not just of the recreation, but of its continuing maintenance?